At seven p.m. sharp, seven nights a week, during the darkest days of apartheid, an incendiary radio broadcast beamed out from Lusaka, Zambia. It began with the clack of machine-gun fire, followed by a familiar call-and-response:

Amandla Ngawethu!

“Power to the People!”

The shooting faded in and out, waxing and waning with the chant.

Hundreds of miles and two countries to the south, people gathered in matchbox homes in Johannesburg’s industrial townships and community centers in the Cape Flats and thatched-roof huts in black homelands to hear the transmission. They hunched over shortwave radios, straining to hear through clouds of static. They listened with the lights off, making sure that nobody had followed them. Secrecy was necessary, because there were informers everywhere. Just hearing this stuff could get you eight years in prison.

ANC Radio Freedom - Kea Rona (It Is Ours) from jonneke k on Vimeo .

The static broke. A sonorous, unmistakably South African voice, all clipped cadences and martial rolling “r”s, announced what listeners undoubtedly already knew: “This is Radio Freedom.”

Before Facebook and Twitter became revolutionary tools, there was radio. For roughly three decades, Radio Freedom was the voice in exile of Nelson Mandela’s African National Congress, the longtime resistance movement that took power in 1994 after the collapse of apartheid.

The station played many roles. It was a recruiting tool, helping fill the ANC’s political posts and the clandestine training camps of its guerrilla army, Umkhonto We Sizwe (“Spear of the Nation” in Zulu). It was also a news station. Apartheid authorities did their best to keep forbidden ideas out of South Africa, and the airwaves were a crucial front in this battle. State radio, broadcast in a welter of languages from English to Zulu and Xhosa, blanketed the country at maximum power. Its relentlessly banal message extolled “traditional” tribal values, warning listeners away from the leftist path.

Guy Berger, a South African radical who did three years in prison for his political activity,observed in an essay last year that the station linked exiled revolutionaries and activists inside the country at a time when communication was virtually impossible. What’s more, he added, Radio Freedom “could provide truth that was absent from most of the legal media in apartheid South Africa.”

Most of all, perhaps, the broadcasts provided inspiration. Taking its cues from Gamel Abdel Nasser’s Radio Cairo and other anti-colonial stations run by newly independent nations across the continent, Radio Freedom’s mere existence suggested that South Africa, too, could shake off white rule. As Sekibakiba Peter Lekgoathi, a historian at Johannesburg’s University of the Witwatersrand, notes, the station “shaped the consciousness and style of struggle of a whole generation of militant youth.”

Radio Freedom was born in 1963, during the first wave of mass resistance to apartheid. In 1960, police opened fire on a crowd of nonviolent protestors in a township south of Johannesburg, killing 69. The Sharpeville Massacre, as it came to be known, prompted the ANC to embrace armed struggle. Mandela, the first commander of the ANC’s armed wing, traveled to Ethiopia for guerrilla training then slipped back into South Africa to help coordinate more than 190 bombings and acts of sabotage throughout the country.

By 1963, though, it was clear that the hoped-for uprising wasn’t coming anytime soon. Mandela had been captured, and the ANC’s ranks were riddled with spies. The first broadcast, then, was an act of defiance—and also, perhaps, a proof of life. In June 1963, the station’s first transmission went out from the armed wing’s hideout on a farm north of Johannesburg. “I speak to you from somewhere in South Africa,” Walter Sisulu, a party leader and Mandela’s mentor, announced. “Never has the country, and our people, needed leadership as they do now, in this hour of crisis. Our house is on fire.”

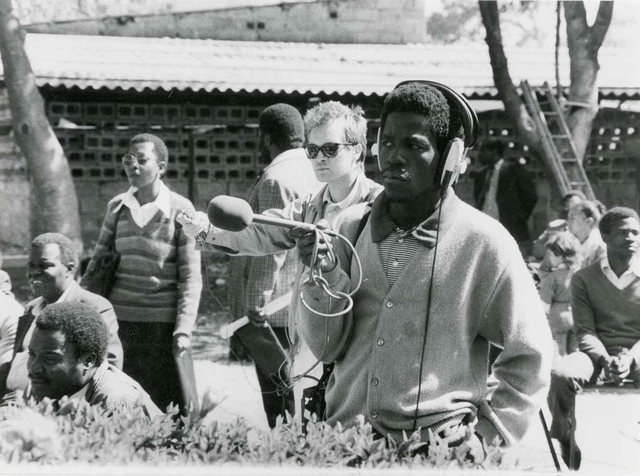

Radio Freedom worker G.Mqwebu reports on a Soweto commemmoration in Lusaka, Zambia, 1966.International Institute of Social History Image Source

Radio Freedom worker G.Mqwebu reports on a Soweto commemmoration in Lusaka, Zambia, 1966.International Institute of Social History Image Source

The authorities raided the farm a couple of weeks later, rolling up much of the ANC’s leadership and putting them all on trial. Mandela was convicted of treason and shipped off to Robben Island, the apartheid regime’s version of Alcatraz. What was left of the leadership, meanwhile, settled into a long exile. Lean years would follow, both for the ANC and for Radio Freedom.

The station reappeared in the late 1960s, broadcasting from black-run countries like Tanzania, Ethiopia, and Madagascar. Over time, however, Zambia—which won its independence from the British in 1964–became the ANC-in-exile’s headquarters. It became home to Radio Freedom, too. The station’s DJs trained all over the world, from the Netherlands to the Soviet Union and East Germany. Upon their return to Zambia, they channeled their expertise, their anger, and their homesickness into these broadcasts.

Each program mixed news of the latest acts of protest or sabotage with songs by the likes of Dollar Brand, whose music was outlawed in South Africa. There were also calls to action. “The time has come for us to acquire weapons, and to pay the white minority regime back in its own coin,” a stentorian voice declared in one 1984 segment. “Pretoria has carried its murderous campaign to extremes. We must now respond to the reactionary violence of the enemy with our own revolutionary violence.”

The announcer counseled his listeners to steal guns from white houses, to make homemade bombs, and to attack isolated police stations. He signed off: “Forward to victory in our lifetime! Amandla Ngawethu!”

Just beneath the surface, though, was a deep longing for home. In one song, as gunfire crackles and women shout, a male voice recites a single refrain, over and over: “We are thinking (of South Africa) / We will come running back with the sound of boots.”

Life in exile wasn’t easy. Low copper prices and economic mismanagement had thrown Zambia into crisis by the 1970s, and resources were scarce. Food was rationed and, at first, the ANC had just one car—a well-worn 1932 Fiat.

Activists had life-and-death worries as well. In 1986, South African jets bombed a refugee camp near Lusaka, killing two and narrowly missing an ANC building. The following year, South African commandos killed five in a predawn raid on an ANC military camp in southern Zambia. In 1988, a car bomb in Lusaka killed an ANC member. As the anti-apartheid activist Conny Braam wrote, “You’re afraid of raids, afraid of strangers, afraid of everything.”

The apartheid state, meanwhile, did its best to jam the transmissions. But at least some of the broadcast always got through. “One thing they couldn’t block out was that opening stanza,” Murphy Morobe, a Soweto student leader, told Lekgoathi. “Now to hear the opening stanza of Radio Freedom with the sound of a machine gun, after that we didn’t even want to hear anymore. That was just sufficient to tell us that we must just carry on with the struggle.”

Over the years, the message spread. Clandestine networks of tape traders recorded the broadcasts—especially ANC President Oliver Tambo’s annual address to the nation on January 8, the party’s anniversary—and distributed them throughout the country. By the mid-1980s the townships were in open revolt, and nobody worried about being arrested for listening to a radio show. The ANC, still in Lusaka, did its best to manage the uprising from afar.

A Los Angeles Times article from 1986 introduces us to a 30-something Soweto man named Sipho who called himself a “human microphone.” Sipho listened to Radio Freedom at night and then, the next morning, repeated what he’d heard, loudly, on the crowded commuter trains headed into Johannesburg. He told the reporter that his fellow riders hadn’t always shown so much interest. Now, though, he said, “They want me to shout out the news, and they leave the train not just talking about the ANC but ready to work for it, to fight for it.”

Ultimately, as South Africa spiraled toward civil war, the apartheid government blinked. Secret delegations shuttled between Pretoria and Lusaka to discuss the unbanning of the ANC, the relaxation of apartheid, and the possibility of a transfer to majority rule. The activists at Radio Freedom, now recording and assembling their shows at a farmhouse outside Lusaka, kept up the pressure. In February 1990, Mandela was released from prison.

A couple of weeks later, Mandela traveled to Lusaka to meet with his ANC comrades in exile. According to the New York Times, a crowd of thousands–many wearing shirts or head wraps bearing his image–greeted him on the airport tarmac. Though the bright summer day clouded over as he spoke, the crowd basked in the liberation leader’s high-wattage smile. “I have often heard the expression that history is not made by kings and generals but by the masses of the people,” he said. “It is … the people of the world who are today making history.”

Chances are, the men and women of Radio Freedom were in the crowd that day. In the months that followed, planning for the transition got under way. The ANC renounced guerrilla war, and the exiles finally returned home. In August 1991, Radio Freedom went off the air. Its microphones and mixing boards were packed up and shipped home to Johannesburg.