Journalist, author and anti-apartheid activist Hugh Lewin has died, aged seventy-nine.

Lewin passed away at his home in Killarney, Johannesburg yesterday.

Born in Lydenburg in 1939, to English missionary parents, Lewin attended Rhodes University before beginning his journalistic career at the Natal Witness in Pietermaritzburg. He also worked at Drum magazine and Golden City Post in Johannesburg.

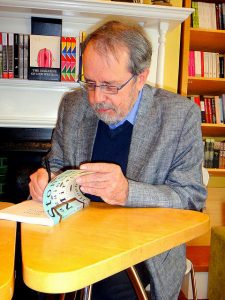

Lewin at the launch of Stones Against the Mirror in 2011. Image source

Lewin at the launch of Stones Against the Mirror in 2011. Image source

In July 1964, when he was twenty-four years old, Lewin was sentenced to seven years in prison for his activities in the African Resistance Movement, a small group of activists that executed acts of ‘protest sabotage’ against the apartheid state, targeting, as Lewin wrote in his 2011 memoir Stones Against the Mirror, victims ‘made of metal and concrete, not flesh and blood’.

Lewin served the full term of his sentence in Pretoria, before leaving South Africa on a ‘permanent departure permit’ in December 1971.

Bandiet Image source

Bandiet Image source

During his years in prison, Lewin secretly recorded his experiences and those of his fellow inmates in the pages of his Bible, and on his release these writings were published in London in 1974 as Bandiet: Seven Years in a South African Prison. Hailed as a classic of prison writing, the book remained banned in South Africa for many years, until it was published by David Philip in 1989.

Lewin spent a decade in exile in London, where he worked as an information officer of the International Defence and Aid Fund and as a journalist for The Observer and The Guardian, followed by another ten years in Zimbabwe, where he became a founding member of the Dambudzo Marechera Trust, before returning to South Africa in 1992. He took up the post of director of the Institute for the Advancement of Journalism in Johannesburg and founded Baobab Press. He was also a member of the Human Rights Violations Committee of the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

In 2003, he was awarded the Olive Schreiner Prize for his memoir, republished in South Africa, with the addition of new material, as Bandiet out of Jail.

Michiel Heyns (Fiction Prize winner), Hugh Lewin (Alan Paton Award winner) and Ray Hartley (Sunday Times editor) at the 2012 Sunday Times Literary Awards Image source

Michiel Heyns (Fiction Prize winner), Hugh Lewin (Alan Paton Award winner) and Ray Hartley (Sunday Times editor) at the 2012 Sunday Times Literary Awards Image source

In 2012, Lewin won the Alan Paton Award for Stones Against the Mirror, with the judges described the book as ‘a beautifully written and intensely personal story of friendship, betrayal and struggle’.

Nadine Gordimer called Stones Against the Mirror ‘a book that was waiting to be written’, adding:

‘There have been many accounts of life in the active struggle against the apartheid regime but this one is a fearless exploration into the deepest ground – the personal moral ambiguity of betrayal under brutal interrogation – actual betrayal of the writer by the most trusted associate and closest friend; and the lifetime question of whether one would have betrayed that same friend under such circumstances, oneself. Hugh Lewin is the man to have faced this with the courage of a fine writer. Unforgettable, invaluable in facing now the ambiguities of our present and future.’

In addition to his non-fiction, Lewin was also the author of the Jafta series of children’s books and the young adult novels Picture That Came Alive and Follow the Crow.

In one of his final public appearances, last February, Lewin was honoured at St John’s College in Johannesburg, which he attended from 1948 until 1957, and whose school history block is now named after him.

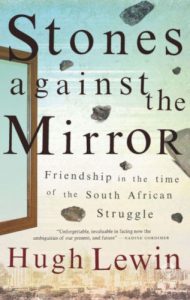

Stones against the mirror Image source

Stones against the mirror Image source

Read Archbishop Desmond Tutu’s Foreword to Bandiet out of Jail:

Quite often in the public hearings of the Truth & Reconciliation Commission I remarked that the revelations of a spirit of forgiveness led us into the presence of something holy. I used to say that we were standing on holy ground and should metaphorically remove our shoes. In South Africa we are blessed by some truly remarkable people of all races, and each one is a person of extraordinary nobility of spirit. Many were involved in the struggle against apartheid and they paid a very heavy price for that involvement.

One such is Hugh Lewin, whose passionate commitment to justice and freedom led him to oppose injustice and oppression with every fibre of his being. For this he paid a heavy price: seven and a half years of incarceration and twenty-one years in exile. This book describes what happened to him and his associates in apartheid’s jails and his encounters with the dreaded Security Branch. Some readers might feel that he is exaggerating when describing the methods of the police, that torture was rare, indulged in only by what some political leaders were to tell the TRC were ‘bad apples” the exceptions in a Force that otherwise behaved impeccably. Hugh Lewin went through sheer hell and emerged, not devastated, not broken, and not consumed with bitterness or a lust for revenge. He amazed, he humbled with his gentleness, his generosity of spirit, his willingness to forgive, when he could have been otherwise, and made a telling contribution to the work of the TRC as a member of its Human Rights Violations Committee. He is endowed with ubuntu – humanness, the very essence of being human. He revea ls another quality of many who suffered: a resilience that prevented him and his fellow ‘politicals’ from going to pieces when they had the stuffing knocked out of them. Instead, they staged plays and found ways to beat the system and to laugh, even at themselves.

Enriched by Hugh’s reflections on postapartheid South Africa, this book reveals again his way with words. He writes like a journalist who is a poet. Or should that be the other way round? And his gentle wry humour is a bonus.

This deeply moving account reminds us where we come from and how high a price has been paid for our freedom. Let us cherish it.