From the book: Book 5: People, Places and Apartheid commissioned by The Department of Education

Apartheid was brought to an end by the struggles of millions of ordinary people in townships, factories and rural areas. The insurrection of the 1980s was fundamentally different from previous struggles against white minority rule, both in its scope and militancy. It represented the most serious challenge to apartheid that had been seen up to that time. The most intense and sustained struggle between the mass democratic movement and the apartheid state occurred between 1984 and 1986. Workers, students, youth, women, the unemployed and villagers in remote rural areas rose up in unprecedented numbers to end their oppression. It was this mass uprising that eventually made the apartheid system unworkable and forced the authorities to seek a negotiated settlement with the liberation movements.

The turning point in the 1980s insurrection occurred from September to November 1984. At that time the African townships of the Pretoria- Witwatersrand-Vaal (PWV, today known as Gauteng) erupted in mass demonstrations and stayaways against the rapidly deteriorating conditions in the townships and the deepening education crisis. The opening act of the revolutionary drama occurred on September 3 in the Vaal townships of Sebokeng, Sharpeville, Evaton, Boipatong and Bophelong. A one-day stayaway was organised to demonstrate against proposed rent increases.

Two weeks later a less successful stayaway was called in Soweto to support the Vaal residents. On October 22 a successful stayaway was organised in the East Rand township of KwaThema. The climax of this mounting revolt was reached on November 5 and 6, when more than a million workers and students embarked on the largest stayaway since the early 1960s. This remarkable action had a huge impact on South African politics. It shook the apartheid government and employers to the foundation, and injected huge confidence into the oppressed population.

An important feature in these struggles was the growing unity in action between township organisations ”” students and civics ”” and trade unions. The unity that was forged between workers and youth took many years to develop, but once it was achieved it was a formidable force for change. Workers and students were at the heart of this alliance. Their respective organisations ”” the Federation of South African Trade Unions (FOSATU) and the Congress of South African Students (COSAS) ”” organised and led these successful struggles. It is to their origins and role that we now turn.

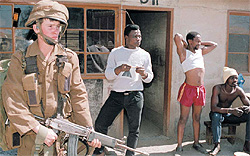

A young South African Defence Force soldier stands guard during the search of a hostel© Graeme Williams / South Photographs

A young South African Defence Force soldier stands guard during the search of a hostel© Graeme Williams / South Photographs

What role was played by the emerging independent unions?

The severe repression that followed the banning of the African National Congress (ANC) and the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC) in 1960 had a devastating effect on the South African Congress of Trade Unions (SACTU), the most important black union movement to emerge in the 1950s.

One measure of the success of independent unions was the spectacular growth in their membership. Between 1979 and 1983 the paid-up membership of independent unions more than quadrupled from 70 000 to 300 000.

FOSATU’s paid up membership increased from 30 100 to 106 460 over the same period. By 1984 it was estimated that the number of black workers organised in trade unions stood at 1,4 million. The government’s legal recognition of black trade unions in 1979 also made it easier to recruit workers.

During the 1960s few black workers were organised in unions, and industrial action virtually ground to a halt. Between 1962 and 1972 the average number of black workers per year involved in any form of industrial action barely exceeded 4 000. At the same time, many black workers moved into semi-skilled and even skilled jobs in industry, making them even more indispensable to the economy. Despite their improved occupational status, black workers continued to receive relatively low wages and were subjected to oppressive conditions on the shop floor. The extreme exploitation of black workers persisted at a time when the South African economy experienced phenomenal expansion, exceeding the growth rates of many industrialised countries. The main beneficiary of the “golden period” of apartheid was the minority white population. This was clearly an untenablesituation.

The industrial calm of the 1960s was shattered in January 1973 when more than 60 000 black workers in Durban went on strike to demand higher wages. In the following years, numerous new workers’ organisations sprang up, especially in the main industrial centres of Johannesburg, the East Rand, Cape Town and Durban. Importantly, former SACTU activists combined with left-wing students and academics to establish new industrial unions.

Although important strides were made between 1973 and 1976, the process of building new trade unions for black workers was often very difficult as workers had to confront conservative employers and a repressive government. Workers had to organise secretly for fear of being victimised or dismissed. Union meetings mostly occurred outside the plants, often in hostels where it was easier to operate without detection.

Strikes were ruthlessly dealt with. For example, the strikes at Heinemann Electrical and Armourplate Glass in 1976 were crushed by a combination of police brutality and employer intransigence. After the 1976 Soweto uprising, the new unions faced a further setback when the government imposed banning orders on 22 union activists.

Despite the various obstacles placed in their path, black workers and their supporters succeeded in building a number of new unions, including the Metal and Allied Workers Union (MAWU), the General Workers Union (GWU), the Chemical Workers Industrial Union (CWIU) and the National Union of Textile Workers (NUTW). These unions were to become the foundation on which the new union movement would be constructed.

Despite the worsening economic conditions in the 1970s, workers continued to press for recognition and for better wages and working conditions, although with mixed success.

untenable”” unable to be maintained or defended against attack or objection

intransigence”” unwillingness to change one’s views or to agree with someone else

An important milestone in the history of unions was reached in 1979 when a number of unions joined forces the Federation of South African Trade Unions. In 1980 another federation, the Council of Unions of South Africa (CUSA), was launched. While FOSATU adopted a largely independent political position, CUSA openly associated itself with black consciousness. FOSATU affiliates were at the centre of a wave of industrial action over the following few years which challenged management on a range of issues including unfair dismissals, health conditions and retrenchment procedures. Workers were becoming more confident and were prepared to assert their power in order to secure basic rights for themselves at plant level.

The economic downturn of the early 1980s caused the number of strikes to increase significantly as workers tried hard to defend their jobs. In 1981 more than 300 strikes were recorded, a significant feat at the time considering the prevailing tough economic conditions and the employers’ offensive against organised workers. The East Rand was at the centre of this strike wave ”” more than 50 strikes involving nearly 25 000 workers took place in the region in only five months. FOSATU affiliates were in the forefront of these shop floor struggles. In 1982 FOSATU unions organised 145 strikes, involving about 90 000 workers, compared to 13 strikes organised by CUSA which involved only 10 000 workers.

FOSATU placed great emphasis on building strong and democratic workplace organisations, based on the principle of workers’ democracy. Shop stewards were the pivotal activists in this new form of unions. They were directly elected by and therefore accountable to workers. FOSATU also focused much of its attention on defending the position of workers at the point of production. Some FOSATU activists feared that becoming involved in community politics would endanger workplace organisation. Others were suspicious of interference by any outside political organisation, including the liberation movements or community political organisations.

To some extent, this view was influenced by a socialist current within the unions which viewed the existing liberation organisations as nationalists and not especially interested in developing a working-class programme and leadership in the struggle against apartheid. Thus in April 1982 the Secretary General of FOSATU, Joe Foster, delivered a speech in which he set out the federation’s objective of creating an independent political organisation for workers.

“FOSATU’s task will be to build the effective organisational base for workers to play a major political role as workers. Our task will be to create an identity, confidence and political presence for worker organisation. The conditions are favourable for this task and its necessity is absolute.”

From a speech by Joe Foster, Secretary General of FOSATU, April 1982

FOSATU certainly did not abstain from links with community organisations. However, at first it did not actively encourage its affiliates to become involved in community or political struggles.

Eventually the mounting struggles in the townships, especially their occupation by security forces, pushed the unions in the direction of greater involvement in township politics. The establishment of community-based shop steward councils on the East Rand was a further indication of the growing links between factories and communities. Students also regularly asked unions for co-operation. They became the critical point of connection between workers and the community, particularly in 1984.

Federation of South African Trade Unions Press Statement The special FOSATU Central Committee meeting wishes to state clearly why FOSATU members participated in the stayaway. We believe that this is necessary because there has been too much focus on reports of violence and too little on the issues.

Our reasons for supporting the stayaway were:

- Ӣ We wanted a clear announcement removing the age limit in the schools.

- Ӣ We wanted democratically constituted SRCs in the schools.

- Ӣ We wanted the army removed from the townships and a stop to police harassment of residents.

- Ӣ We wanted a suspension of rent and bus fare increases.

These factors directly affected our members as workers and parents and we took the action because of this. We therefore totally condemn the detention of FOSATU office bearers and officials who carried out FOSATU instructions. We call for the immediate release of Chris Dlamini, Moses Mayekiso and Bangilizwe Solo and for the release of all persons detained under the Security Legislation.

FOSATU is not prepared to stand by and watch its leadership being detained. Detailed and far ranging decisions were taken by the special Central Committee to protect FOSATU and ensure the release of those detained. These will be reported back to all Regions and affiliates for their approval and implementation. The first report back will be to the FOSATU Executive on the 17th November.

FOSATU sees this as a direct attack on unions and will be contacting other unions to support it in its actions.

The proposal made by the Transvaal Region for a “Black Christmas” will be referred back to all Regions and affiliates of FOSATU for consideration as a national campaign.

The Central Committee committed itself to the full support of CWIU and the SASOL workers.

[FOSATU CENTRAL COMMITTEE]

Source: Historical Papers, University of the Witwatersrand, FOSATU Archives, AH/999/C3.14, Pamphlets

How did students contribute to the uprising?

The Soweto uprising of 1976 placed students in the frontline of the battle against apartheid. Over the next decade and a half students and youth continued to play this vanguard role, for which they bore the brunt of state repression. The state’s banning of Black Consciousness student organisations failed to halt the emergence of vibrant and militant student movements.

In 1979 student struggles entered a new era with the establishment of the Congress of South African Students (COSAS) and the Azanian Students’ Organisation (AZASO), which organised secondary and tertiary students respectively. AZASO initially agreed with black consciousness ideas, while COSAS aligned itself strongly to the Congress Movement. In fact, COSAS was established by former political prisoners who had become underground ANC operatives. One of these was the first president of the organisation, Ephraim Mogale. COSAS’s public association with the ANC brought it quickly into conflict with the state, which detained its senior activists at the end of 1979. Despite these setbacks, the student movement continued to march ahead, continually educating, organising and mobilising its constituency against the rapidly deteriorating conditions in the schools.

By the late 1970s most schools in black areas were already in the midst of a serious crisis. They were overcrowded and in varying states of disrepair, educational and recreational facilities were mostly absent, the majority of teachers were either under-qualified or unqualified, principals tended to be authoritarian, and corporal punishment was an integral part of the culture of the schools. Overcrowding in East Rand schools probably reflected the national situation. In Katlehong in 1978, between 50 and 88 students crammed into single classrooms. In Thokoza the number climbed as high as 96. The situation worsened in the early 1980s as the number of black students enrolled in secondary schools rocketed to over a million. As a result, the number of failures in Katlehong schools surged from 2 336 in 1979 to a staggering 41 627 in 1983.

Increasingly, students refused to accept these intolerable conditions. The school boycotts of 1980, which originated in the Western Cape, saw thousands of students protesting against the deteriorating conditions in schools. Mass marches occurred all over the peninsula and Student Representative Councils (SRCs) were established in most schools. A“Committee of 81”, made up of leaders from the secondary schools, led the boycott. The boycott soon spread to the rest of the country. It was particularly strong in the Eastern Cape, where it continued well into 1981. The police intervened with characteristic brutality to put down these protests. Many student activists were detained.

Although COSAS did not play a leading role in these struggles, it benefited from the politicisation of large numbers of students. COSAS’s slogan ”” Each One, Teach One ”” became a rallying point for students across the country. Its membership and structures grew significantly during the wave of school boycotts in the early 1980s. By 1984 it had established centres throughout the country, although its strongest bases remained in the PWV and the Eastern Cape. Thereafter, COSAS began to mobilise in earnest on a number of educational issues affecting mainly African secondary school students.

COSAS campaigned tirelessly to force the Department of Education and Training (DET) to give in to its main demands. These demands included the recognition of democratically-elected SRCs, the abolition of the 20-year age limit for students, the abolition of corporal punishment, and an end to sexual harassment of female students by male teachers. The struggle over these grievances continued in 1982 and 1983, during which time there were sporadic outbursts of school boycotts and other forms of demonstration.

Students had also become increasingly involved in community struggles, and supported strikes by organised workers. This indicated a growing awareness among students that their struggle around educational issues could not be separated from the broader struggle. Students began to include civic demands in their list of demands, indicating the growing unity in action between the different sectors in the struggle against apartheid.

Students were in the forefront of the campaign to boycott the Black Local Authority elections in 1983. COSAS members were instrumental in the establishment of Youth Congresses and often comprised the leadership of branches.

By 1985 student and youth organisations had been established across the country and were often in the forefront of militant struggles, especially against the security forces. They were also instrumental in the struggles that had erupted in the bantustans. Indeed, a key feature of the mass uprising of the 1980s was the absolutely critical role played by students and youth. Together with organised workers, they were the main agents of change in the country at the time.

Victor Kgobe vividly remembers the adverse conditions at his old school:

“During those days conditions were very harsh at Mazambane primary school. The school couldn’t accommodate all of us. As a result some classes would basically attend at church sites. You were speaking about a situation where we didn’t have equipments, we didn’t have desks, most of us actually sat on the floor, there were a lot of broken windows, they were not being fixed and those were the conditions. There were not enough toilets. And we basically didn’t have laboratories. And the other aspect of it is that it was a kind of a top-down structure where basically the principal will instruct the teachers and the teachers will basically instruct the students”¦. And there was also a question of corporal punishment where we were severely beaten. In those days it was acceptable, unlike now, to severely punish learners.”

Dumisa Ntuli, a leading student activist from Thokoza, recalls:

“The key demand was around corporal punishment, because these teachers used to beat students. There was no single form of corporal punishment. They used to sjambokyou anywhere, which was difficult for students to accept. It was the rallying point for us as well.”

Mando Sekgatle, a prominent female student activist from Alexandra township, joined Cosas in 1979 because ”¦

“”¦ there was that prefect system. So we did not want the prefect system. We were being corporally punished, harassed, and we were not allowed to say anything. So we wanted to form an SRC instead. So we started by forming COSAS. So I joined COSAS as a South African student. I was the secretary.”

What factors contributed to the township uprising?

Apartheid had consignedthe black population to racially-defined townships which were characterised by deepening socio-economic difficulties, spiralling into a full-blown crisis from the early 1980s. After the government had established the huge dormitory townships in the 1950s and 1960s, it invested very little money in the further development of those areas, preferring to prop up the new bantustan administrations. As a result, almost every aspect of township life suffered.

sjambok ”” a long stiff whip, originally made of rhinoceros hide

consign someone to”” to put someone in a certain place in order to be rid of them

The housing crisis

Perhaps the most graphic illustration of the crisis was the rapidly developing housing crisis. For example, between 1973 and 1979 fewer than 7 000 houses were built on the East Rand ”” less than 100 houses per year in each township. During that time the urban African population had nearly doubled.

In Katlehong, the East Rand’s largest township, the population increased from 95 000 to approximately 200 000 between 1970 and 1980. The result was a massive housing shortage. In Katlehong the official housing waiting list in 1981 stood at 4 000. The situation was aggravated by the mass influx of people escaping the grinding poverty in rural areas. The number of shack dwellings grew rapidly. The number of backyard shacks in Katlehong grew fourfold (from 8 000 to 34 000) in the short space of two years. In Soweto the number of families living in shacks had increased to 23 000 by 1982. Similar situations existed in most townships across the country.

The state acknowledged the severity of the crisis but refused to allocate the required financial resources to resolve the problem. It limited its own investment in township infrastructure and deregulated housing in the townships. The decision to give the private sector a greater role in township housing provision was also intended to promote the development of middleclass home ownership in the townships. However, very few township residents could afford to purchase the houses in the new “middle-class” areas.

The state’s policies were based on the principle that townships should become self-financing. The government’s refusal to provide anywhere near adequate funding for township development was the root cause of the crisis that enveloped the townships in the early 1980s. Traditional sources of income in the townships, such as profits from beer halls and the services levy, had dried up in the 1970s. Thus the only source of additional income available was the increase of house rentals. The pervasive poverty that characterised townships made this a very explosive issue.

Rent increases

At the same time, the state introduced changes to the local administration of townships, partly to shift the political responsibility for the financial squeeze on residents to local conservative politicians. New local authorities were established through the Community Councils Act of 1977 and the Black Local Authorities Act of 1982. The councillors enjoyed little support in their communities, as was evidenced by the local elections. In the 1983 elections only 8% of adult residents bothered to vote. The legitimacy of these structures was compromised by their inability to stop the rapid decline

of living conditions and by their decision to increase rents.

Opposition developed wherever rent increases were proposed. For example, the Soweto Civic Association mobilised resistance against the proposed increases in 1979, and forced the authorities to back down.

Similar local protests occurred all over the PWV. In the early 1980s the government announced its intention to upgrade the infrastructure of townships but made it dependent on contributions from residents. Thus the Katlehong Council planned to spend R15 million on the provision of electricity but expected each resident to contribute R10,50 a month in addition to other service charges. Sharp and burdensome rent increases were announced for most townships during this period. In Katlehong rents were expected to increase from R18,85 to R28,85. In Daveyton rents were set to increase by R14. The situation was particularly serious in the Vaal where rents increased by a massive 400% between 1978 and 1984.

The inability of residents to meet these high costs was illustrated by the huge arrears accumulated at the time. In 1983 the eleven townships of the East Rand owed more than R3 million, with Katlehong alone owing more than R1,5 million. It was estimated that nearly 35 000 households in the Vaal were in arrears by early 1984. The majority of township residents were too poor to pay these increases. The economic recession and consequent unemployment of the early 1980s further aggravated the situation.

The launch of the Congress of South African Trade Unions in Durban in 1985© Paul Weinberg / South Photographs

The launch of the Congress of South African Trade Unions in Durban in 1985© Paul Weinberg / South Photographs

Residents’ increasing inability to carry the mounting costs being shifted onto their shoulders, and the state’s determination to make them pay, created the conditions for a serious confrontation. The state’s decision to introduce steep rent increases throughout the PWV in early 1984 thus ignited an already volatile situation.

Civic associations

The mounting dissatisfaction with poverty and the mismanagement of the townships found organisational expression in the formation of civic and residents associations. The Soweto Civic Association and the Port Elizabeth Black Civic Organisation were among the first of a new brand of mass civic organisation to be established in the late 1970s. They were soon followed by the Cape Areas Housing Action Committee which organised in the coloured areas of the Western Cape, the East Rand People’s Organisation, and the Vaal Civic Association. Women played a particularly prominent role in these civic organisations.

They were constantly in the forefront of the struggles against rent increases and the demolition of shacks. The civics played a leading role in the initial mobilisation of communities and laid the foundation for the subsequent mushrooming of mass democratic structures, including organs of people’s power.

A Katlehong resident echoed the prevailing view in the townships about the increased financial burden and the role of councillors:

“I think Katlehong township has gone from bad to worse. I was shocked the other day to hear that rent and other services have been increased without the residents being notified. Our township should be the last to increase the service charges because it is a very lousy place.... The municipal dirt bins have not been collected for at least four months now. When residents applied for electrification, unfortunately you have to pay R350 apart from the so-called master plan which you pay for dearly at R7,50 per month. Payment of the master plan is not R13,50 per month ”” 95% of councillors in our township are very rich people.”

What happened during the township uprising?

From the late 1970s, workers and youth began to forge a militant alliance against what was identified as the “common enemy” ”” the state and bosses. In 1979 workers and the community mobilised a boycott of Colgate-Palmolive products to support the workers’ demands for recognition of their union, the Chemical Workers Industrial Union. So successful was the mobilisation that management gave in the day before the strike and boycott were scheduled to begin. In 1980 youth mobilised support in the communities for meat workers who were in dispute over the recognition of democratically-elected workers’ committees. The red meat boycott enjoyed considerable success. Similar solidarity campaigns were organised in the Fattis and Monis and Wilson Rowntree disputes. At the same time, a number of worker leaders such as Moses Mayekiso, Chris Dlamini, Sipho Kubekha and Sam Ntuli became more involved in community struggles and were instrumental in the formation of civic organisations on the East Rand and Alexandra. Also, some students who began their political careers in the education struggles of the late 1970s and early 1980s joined the union movement as organisers and activists.

A key moment in the mobilisation against apartheid was the launch of the United Democratic Front on 20 August 1983. The UDF was explicitly Charterist and united nearly 600 organisations under its banner. The front was created to oppose elections to the Tricameral Parliament in coloured and Indian areas, but it was soon transformed into the leading liberation

movement in the country.

Most unions decided not to affiliate to the UDF, in order to safeguard their independence. A handful of unions, like the South African Allied Workers Union, did join the UDF. Nonetheless, a relatively close relationship developed between the UDF and FOSATU, although it was often strained by political and strategic differences. FOSATU threw its weight behind the Tricameral boycott campaign.

The successful boycott of the Black Local Authority Elections, the mounting student boycotts, the strike wave of the early 1980s, the launch of the UDF and the proliferation of local community organisations signified a critical change in the national political situation. The political pressure that was building from the late 1970s eventually exploded into a mass rebellion in the PWV.

The regional insurrection started in the Vaal townships in response to the Lekoa Town Council’s announcement of a rent increase of R5,90 despite overwhelming evidence that residents could not even afford the existing rents. The Vaal Civic Association led the protests against the Town Council throughout August. On September 2 it was decided that residents should refuse to pay their rents. The stayaway the following day was supported by up to 60% of the workforce. The police reacted viciously to the demonstrations in the townships that day. Scores were injured, and 31 were killed. The fires of resistance quickly engulfed other townships in the PWV. In Soweto, the Release Mandela Committee called for a stayaway in solidarity with Vaal residents. The action was not well organised, however, and only 30-65% of workers heeded the call.

From this point on, the centre of the struggle shifted to the East Rand. In October COSAS in KwaThema mobilised parents to support student demands. At a meeting held on 14 October and attended by 4 000 people, a parent-student committee was established to lead the struggle.

Significantly, leading trade unionists, including Chris Dlamini (the president of FOSATU), sat on the committee. After failing to get a positive response from the government, the committee called for a stayaway. The local stayaway of 22 October was a resounding success, as more than 80% of workers stayed at home.

Factory-based struggles and worker militancy were also on the increase. In the first ten months of 1984 almost 120 000 workers were involved in 309 strikes (more than double the number of workers involved during the same period in 1983). The relationship between unions and communities was further cemented by the Simba Quix boycott campaign that was launched in August 1984. The scene was set for a major demonstration of unioncommunity power. The showdown with the state came to a head in November 1984. The initiative came from COSAS, which called on unions to support its struggle.

The FOSATU Central Committee met on October 19-21. It resolved to support the students in their demands and also mandated the representatives from the Transvaal to represent FOSATU on the Stayaway Co-ordinating Committee. Seven union representatives were nominated, including Moses Mayekiso, Chris Dlamini and Bangilizwe Solo. The Transvaal Regional Stayaway Committee was formally constituted on 27 October and comprised 37 organisations. The four-member co-ordinating committee was made up of Moses Mayekiso, Themba Nontlane, Oupa Monareng and Thami Mali. It was decided to call a regional stayaway on 5 and 6 November. Numerous meetings were held in factories, schools, townships and hostels. More than 400 000 pamphlets were distributed. In addition to supporting students’ grievances, the Stayaway Committee called for the withdrawal of the army from the townships and for a suspension of rent and bus fare increases.

The regional general strike was a phenomenal success. More than 800 000 workers and 400 000 students stayed at home. Support for the action was particularly good on the East Rand and in the Vaal because of the strength of the unions in those regions.

What happened after the uprising in the PWV?

The state responded to the PWV uprising with even more repression. In October thousands of troops poured into the Vaal townships during“Operation Palmiet”. From this time onwards, the occupation of townships by the security forces became a common feature of the country's landscape. Scores of union and student activists were arrested. On 21 March 1985, the anniversary of the Sharpeville massacre, the police killed more than 20 people in Uitenhage's Langa township. The Langa massacre reflected the growing brutality of the security forces in their attempts to quell mass movement against apartheid. In July the state went a step further by declaring a State of Emergency in 36 magisterial districts in the PWV and Eastern Cape. In August it banned COSAS.

The state's clampdown merely added fuel to the flames of resistance. The success of the November stayaway spurred other regions into action. Scores of local authority councillors were forced to resign, rendering ineffective the government's experiment of shifting the political responsibility for unpopular policies onto conservative local politicians. Rent boycotts became extremely common, and consumer boycotts were launched in the Eastern Cape. From the perspective of the authorities, the townships had become ungovernable.

Communities across the country set up street committees or organs of “people’s power” to run the townships. By the end of 1985 virtually every urban township had become part of the insurrection. Increasingly, smaller towns and rural areas were drawn into the mass movement. School boycotts continued unabated and youth organisations were also increasingly drawn into direct confrontations with the armed forces.

Perhaps the most significant event of 1985 was the launch of the Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU), which grew mainly out of FOSATU. COSATU was by far the largest and most powerful union movement in the history of the country. It immediately stamped its authority on the liberation struggle by simultaneously tackling key workplace issues and challenging the state. It called massive general strikes over the following few years, involving millions of workers. By the mid-1980s it had become apparent that the end of apartheid was in sight.

WORKERS, WORKERS, BUILD SUPPORT FOR THE STUDENTS STRUGGLE IN THE SCHOOL

For many month 1000’s and 1000’s of us have struggled in the schools. We students united in massive boycotts to FIGHT FOR OUR DEMANDS:

- STUDENT REPRESENTATIVE COUNCILS (SRC) IN EVERY SCHOOL

- AN END TO ALL AGE RESTRICTIONS

- FOR THE REINSTATEMENT OF EVERY SINGLE EXPELLED STUDENT

- FOR FREE BOOKS AND SCHOOLING

- FOR AN END TO ALL CORPORAL PUNISHMENT

- IN PROTEST AGAINST THE NEW CONSTITUTION WHICH EXCLUDES THE MAJORITY OF PEOPLE, IS RACIST AND ANTI-WORKER LIKE YOU WORKERS:

we want democratic committees under our control (SRCs) to fight for our needs.

LIKE YOU WORKERS: we students are prepared to fight all and every dismissal from our schools.

LIKE YOU WORKERS: we defend older students from being thrown out of our schools, just like you defend old workers from being thrown out of factories.

LIKE YOU WORKERS: demand free overalls and boots so we students demand free books and schooling. And students don’t pay for books and schools. IT IS THE WORKERS WHO PAY.

JUST AS THE WORKERS: fight assaults against the workers in the factory so we students fight against the beatings we get at school.

From Cradock to Pietersburg, from Paarl and Capetown to Vereeniging, from Thembisa, Saulsville, Atteridgeville, Alexandra, Wattville, Katlehong we have come out in our 1000’s in mass boycott action.

WORKERS, YOU ARE OUR FATHERS AND MOTHERS, YOU ARE OUR BROTHERS AND SISTERS. OUR STRUGGLE IN THE SCHOOLS IS YOUR STRUGGLE IN THE FACTORIES. WE FIGHT THE SAME BOSSES GOVERNMENT, WE FIGHT THE SAME ENEMY.

Today the bosses government has closed many of our schools.

OUR BOYCOTT WEAPON IS NOT STRONG ENOUGH AGAINST OUR COMMON ENEMY, THE BOSSES AND THEIR GOVERNMENT.

WORKERS, WE NEED YOUR SUPPORT AND STRENGTH IN THE TRADE UNIONS.

WE STUDENTS WILL NEVER WIN OUR STRUGGLE WITHOUT THE STRENGTH AND SUPPORT FROM THE WORKERS MOVEMENT. ** PREPARE FOR A JOINT MEETING OF STUDENTS AND WORKERS TO DISCUSS CONCRETE SUPPORT FOR THE STUDENTS STRUGGLE. **

Workers, we students are ready to help your struggle against the bosses in any way we can.

But today we need your support.

[Issued by COSAS Transvaal Region]

Source: Historical Papers, University of the Witwatersrand, FOSATU Archives, AH/999/C3.14, Pamphlets.